In public discussions about climate change, even among us Americans who understand that it is happening and who acknowledge that we are causing it, the topic usually is limited to carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels-- coal, oil, and natural gas. These are the sources for more than 85% of all commercial energy that we use in the U.S.

By adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, we enhance the Earth's greenhouse effect. The result is that the Earth's atmosphere absorbs heat that normally would be re-radiated into space. This is well understood by climate scientists and most others.

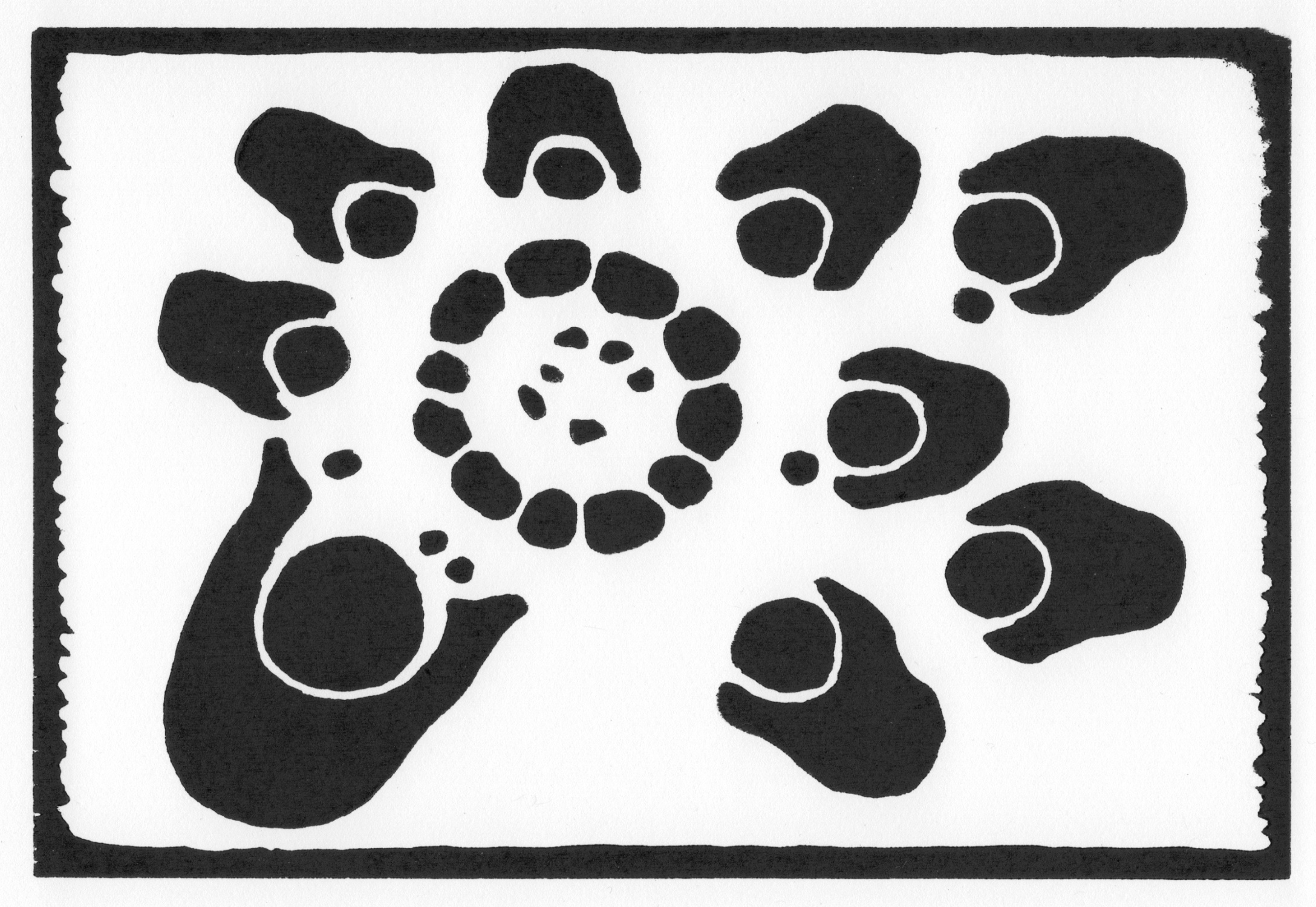

What most folks don't know or haven't been told about are the several climate feedback loops that are being set in motion by our planet-warming carbon emissions. The illustration below briefly explains one of the more apparent feedback mechanisms, the ice-albedo feedback loop.

If most people understood this "run-away" feedback effect, we would probably conclude that even the most drastic emission-limiting proposals are woefully inadequate to deal with the problem of global change. Here are summaries of three popular approaches that have been advanced by people who care. These have mostly been dismissed as too drastic.

1. We should reduce our carbon emissions to 80% of current levels by 2020. Or pick any percentage or any year.

2. We should stabilize atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations at 350 ppm. Or pick any concentration.

3. We need to be carbon-neutral by 2050. Or pick any date.

By understanding the climate feedback loops one might conclude that an even more radical approach is necessary-- we must become carbon-negative yesterday. This means that we immediately emit no more carbon at all and start planting trees to temporarily sequester some of the atmospheric carbon dioxide in plant tissue. (Of course, we must also revolutionize our land-use strategies.)

These change-enhancing feedback loops take on a life of their own. So, if we stabilize the greenhouse effect today at present levels, the warming and ice-melting trend will continue which will cause more warming and ice-melting, etc. The loop will disappear only after there is no more ice and snow on the planet and after the climate is warm enough that no more snow falls and no ice forms.

We hear from scientists and other observers that global warming is happening faster than predicted. Most of the predictions have not included feedback loops.

The ice/albedo feedback loop is just one of several that we will discuss later.