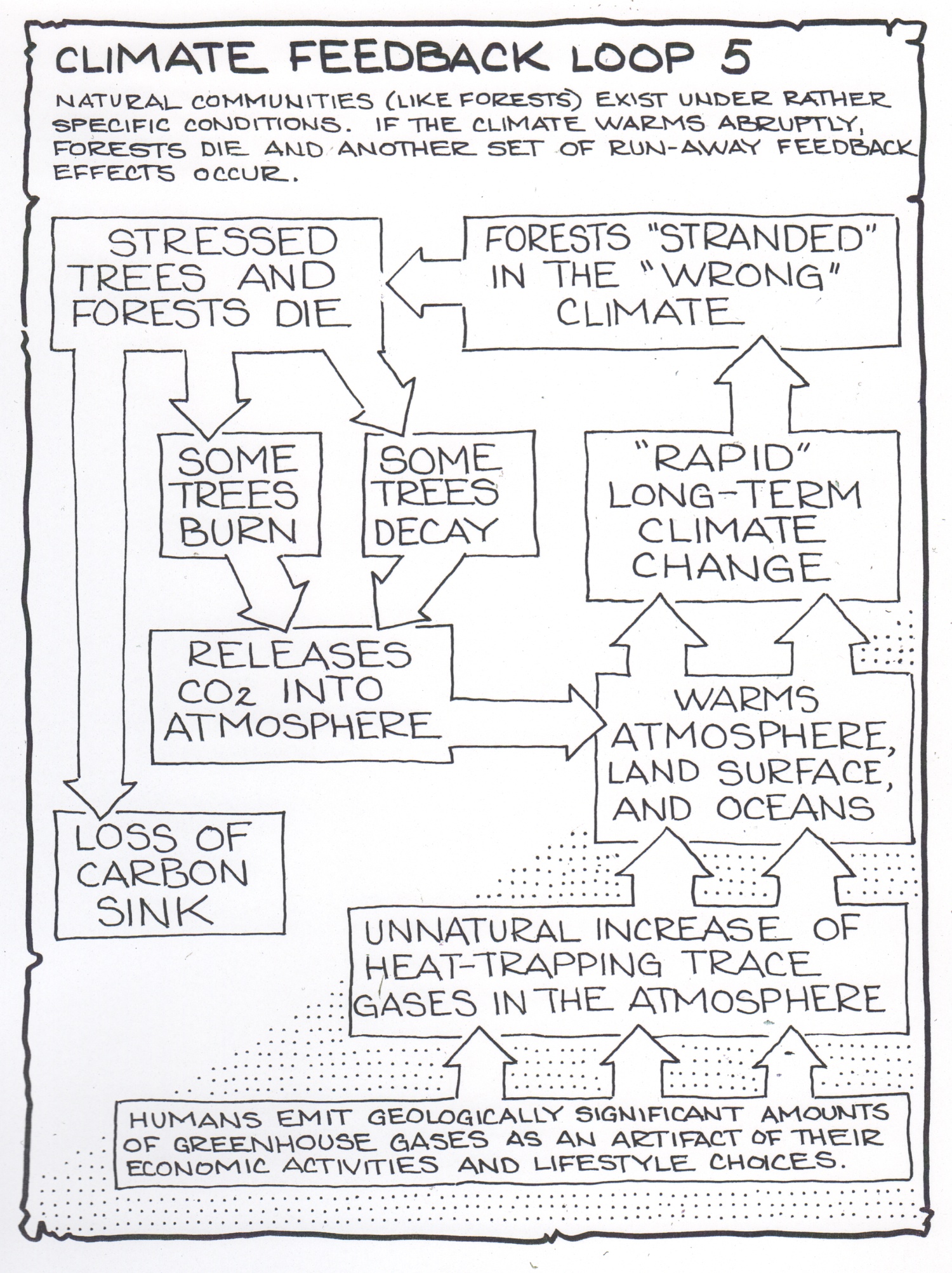

Here's an example of what started to be a sketchbook exercise-with-letters turning into an environmental science commentary.

In the context of evolved systems and engineered systems, change is destabilizing.

This was a perennial final exam question in my environmental science/environmental issues classes at the university.

I rationalized that the correct explanation for students was that currently thriving evolved systems (such as ecological communities, global climate systems, etc.) are the products of a period of relatively stable conditions. Yes, change happens continually, but usually on small scales and of short durations. Beyond the range of benign, creative change, drastic change is destabilizing. And the greater the change, the more extensive the change, and/or the more rapid the change, the more destabilizing the change is.

The logic of the concept is demonstrated in a simple experiment with a familiar engineered system. The next time you take your internal combustion car in for an oil change, make a change. Have the mechanic drain the oil from the crankcase and replace it with coolant. Have him drain the coolant from the cooling system and replace it with oil. This represents a change from the normal conditions. See if it affects the car's performance; see if this change destabilizes the engineered system..

Now, on a larger scale, we could see if we could destabilize the Earths's climate system by increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by 35%. For the planet, this experiment, in its effect, is similar to the exercise with the car. The big difference is that most people have more sense than to drive a car with no coolant, but those same people don't understand the effect of their activities on the energy balance of the planet. We have reached the 35% increase mark and are heading for 50%.

Dramatic change is not the end of the world for all organisms- just for those that were adapted to the "relatively stable" previous conditions.

Unfortunately, the playfulness of the graphic (below) downplays the seriousness of the concept.